Learn how to change behavior.

The world's largest collection of resources and data on behavioral science.

Behavior change and behavior design models

MODELS

Attention, Belief, Choice, Determination

TYPE

Behavior design process / heuristics

ORGANIZATION

OECD

MODELS

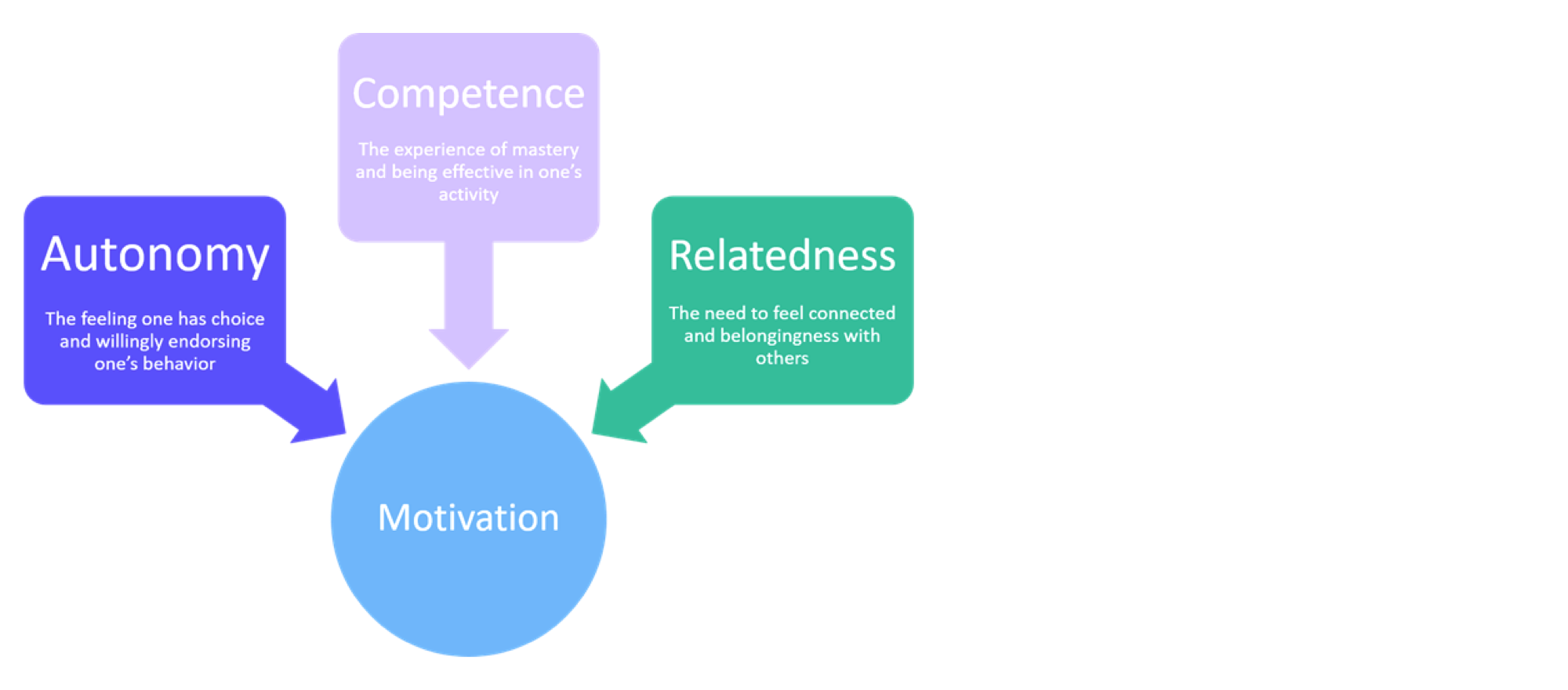

Self-Determination Theory

TYPE

Behavior model

PEOPLE

Richard Ryan, Edward Deci

MODELS

COM-B | Capability, Oppportunity, Motivation → Behavior

TYPE

Behavior model

PEOPLE

Susan Michie, Robert West, Maartje van Stralen

MODELS

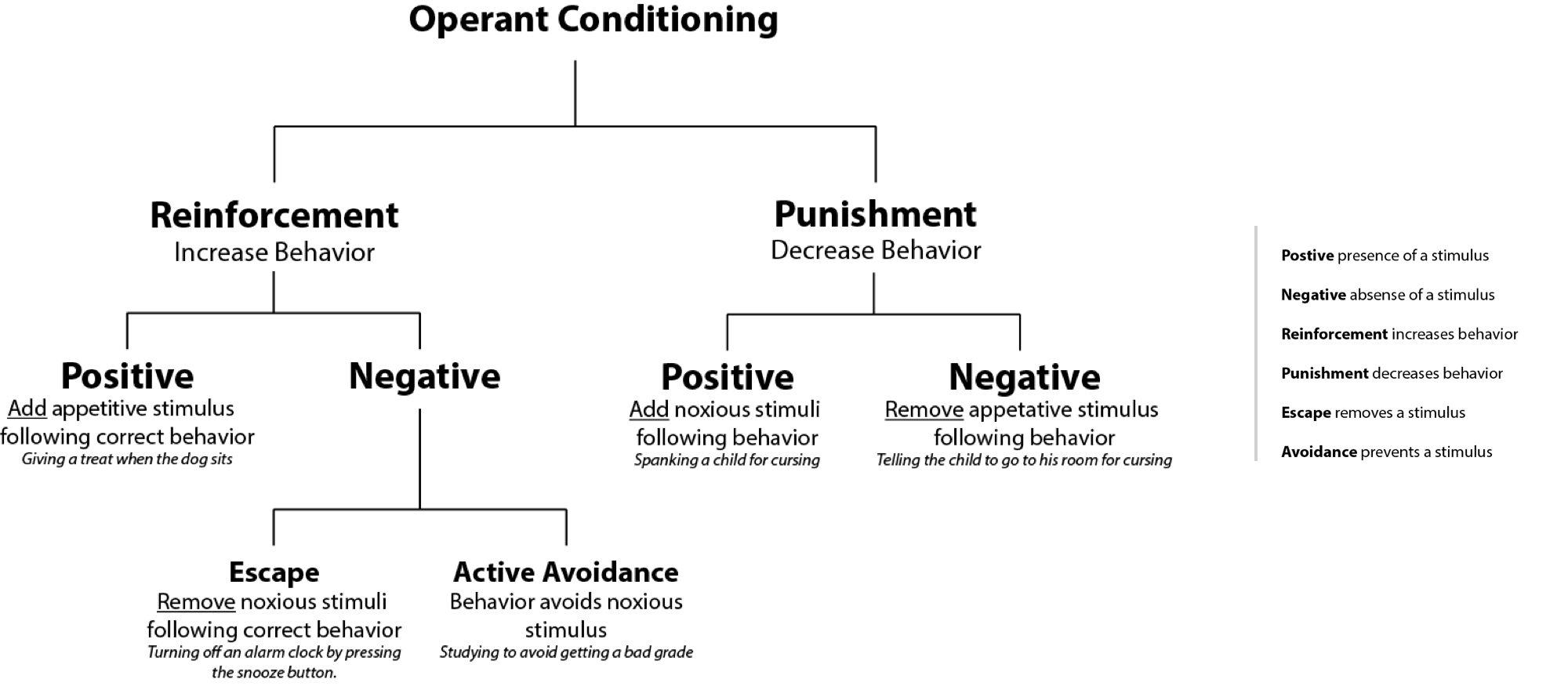

Operant Conditioning

TYPE

Behavior model

PEOPLE

BF Skinner, Edward Thorndike

MODELS

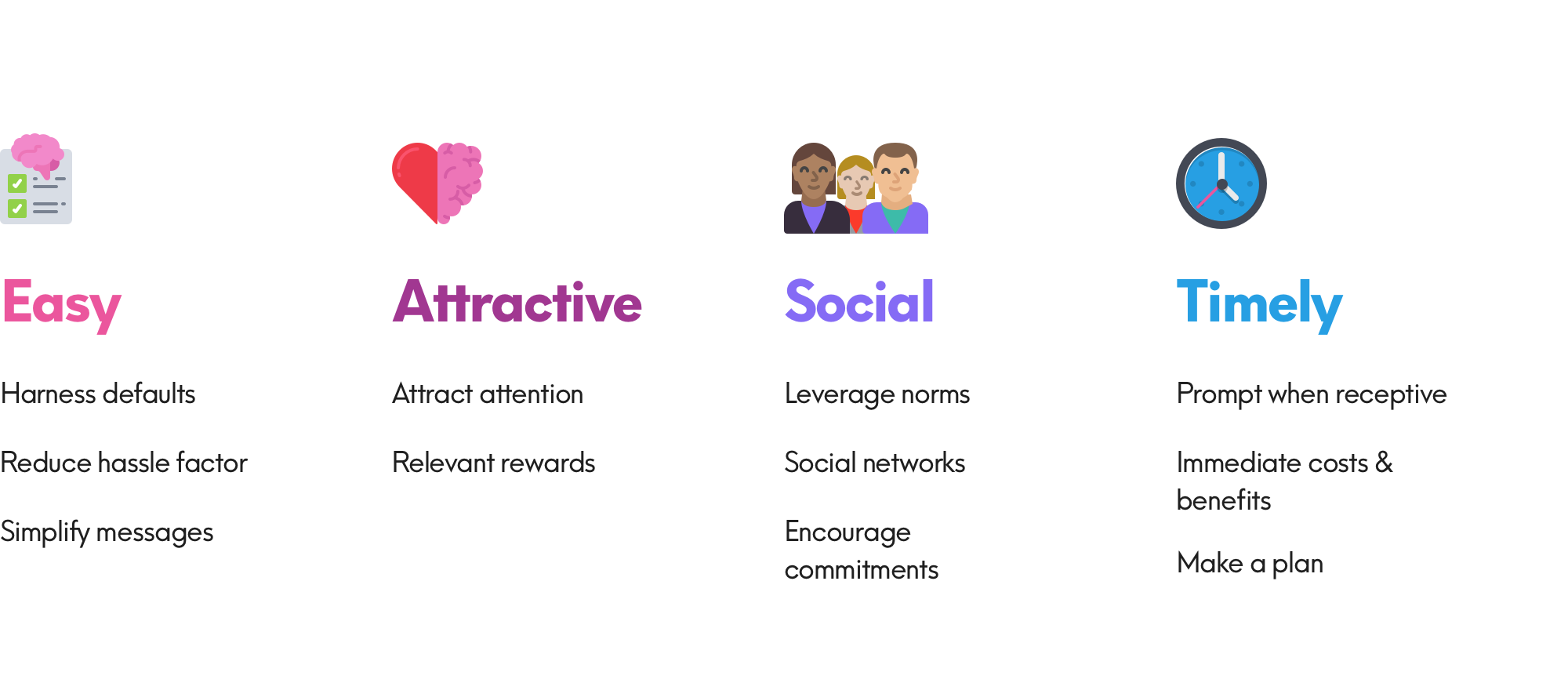

EAST | Easy Attractive Social Timely

TYPE

Behavior design process / heuristics

PEOPLE

Owain Service, Michael Hallsworth, David Halpern

ORGANIZATION

UK Behavioural Insights Team (BIT)

MODELS

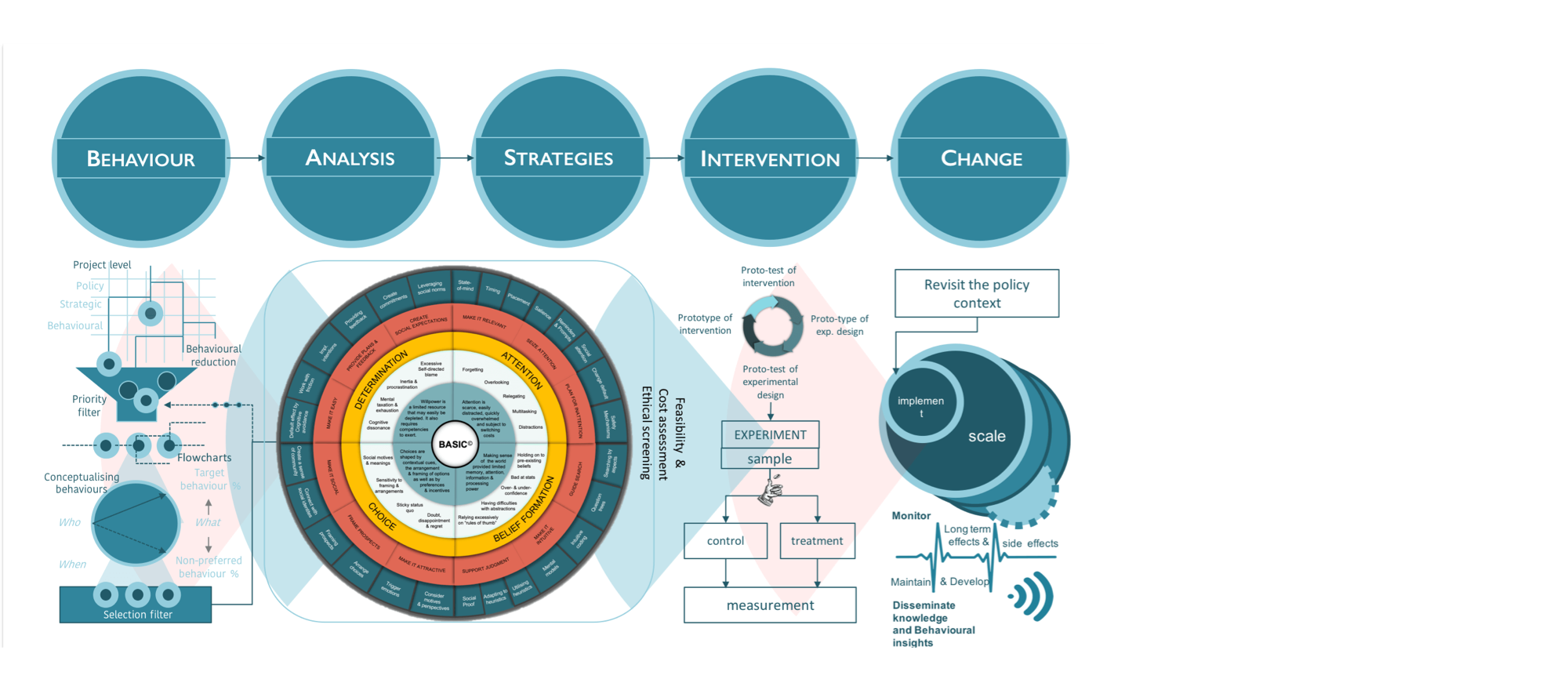

BASIC | Behavior, Analysis, Strategy, Intervention, Change

TYPE

Behavior design process / heuristics

ORGANIZATION

OECD

Tactics that change behavior

TACTICS

Clawback Incentives

Clawback incentives refer to a framing effect applied to rewards where participants are intended to experience losing the reward via noncompliance rather than accruing it for successful performance of the behavior.For example, a hypertension management program may credit its participants $200 at the beginning of the month, and reduce or "claw back" the amount by $3 each time the patient does not take their medication. The alternative would be starting the month at zero or the previous ballance and adding $3 each time the patient takes the medication.

TACTICS

Commitment Devices

Commitment devices are tools that attempt to bridge the gap between a person's initial motivation to perfrom the behavior and the typical pattern of noncompliance as time goes on.One prominent example is the "Ulysses Pact," where Filipino banking customers were offered the option to enroll in an account where their ability to make withdrawals would be limited. In a study by Ashraf and Karlan (2005), participants with the commitment account saved 81% more than those with typical accounts. There are many other examples of commitment devices. Temptation bundling is a form of commitment device where people only engage in an enjoyable activity when it's simultaneous with an activity they intend to do more (for example, only listening to a certain podcast or audiobook while walking on a treadmill). Pre-paying for a service is a basic form of commitment device, and one used by Dan Ariely when he intended to increase his fruit and vegetable consumption. He paid for a year of biweekly deliveries from a local CSA program up-front.

TACTICS

Coaching or Counselling

Coaching or counselling here refers to having a trained person provide guidance to someone attempting a behavior. Many mental health and lifestyle programs utilize coaching in various forms, including phone calls, video chat, text messaging, or in-person sessions. Some programs have replaced some or all of these traditionally human-delivered touchpoints with AI or rules-based interactions.

TACTICS

Active Choice

Active choice, sometimes referred to as enhanced active choice or forced choice, refers to removing default options and often increasing the salience of potential decisions through emphasizing the consequences of one or more of the options. Coined by Punam Anand Keller and colleagues in 2011, it was originally intended to address concerns around paternalistic nudging for use in situations where forcing the default option may be considered unethical. In one of the original studies, CVS customers were given the choice to enroll in automatic refills of medications via delivery. The choices they were presented were ""Enroll in refills at home"" vs “I Prefer to Order my Own Refills.”

TACTICS

Automation

Automation refers to having another person, group, or technology system perform part or all of the intended behavior. A prominent example is Thaler & Bernartzi's Save More Tomorrow intervention, which invested a portion of employees' earnings into retirement funds automatically and even increased the contribution level to scale with pay raises. Other examples include automatically scheduling medical appointments so the patient needn't do it themselves and mailing healthy recipe ingredients to the person's home to reduce the burden of shopping.

TACTICS

Behavioral Economics

Behavioral economics is the exploration of how people make consequential decisions where psychological and sociological factors may influence the outcome or process. It is often considered the fusion of economics and psychology (which itself was an interdisciplinary field entailing medicine and philosophy). The exploration of psychological factors in economic decision-making, including deviation from rationality, traces well back to classical and neoclassical economics (i.e. Gabriel Tarde, Wilfredo Pareto, and John Maynard Keynes) and prior to psychology becoming a formal discipline. Behavioral economics is often associated with behavior change tactics like smart defaults, reducing friction or barriers, increasing salience, incentives, active choice, and commitment devices.

TACTICS

Checklists

Checklists are an age-old tactic for remembering to do certain tasks. Checklists are sometimes used to measure behaviors that should take place with a certain frequency, e.g. every day or X times per week, and other times, to ensure certain steps are followed every time a person does a complex behavior.For behavior designers, the challenges of checklists often entail choosing the right behaviors, breaking them down to the correct level of granularity for a given population, and serving them up in the proper context or sometimes with personalization. They are likely underutilized and consistently improve the performance of even experts, like pilots and surgeons.

TACTICS

Behavioral Activation (BA)

Behavioral activation is a therapeutic approach that typically pairs activity scheduling with either monitoring tools or goal-setting. For example, someone might aim to balance activities they "should" do but underperform, like self-care behaviors, with activities they enjoy. Users of this technique may also track which activities cause certain cognitions or affective states, like those associated with depression.

Products that change behavior

PRODUCTS

Accupedo

Behaviors

Physical Activity

Tactics

Education or Information, Reminders, Cues +3 more

PRODUCTS

2Morrow Chronic Pain Program

Behaviors

Mental Health & Self-Care, Other, Disease Management

Tactics

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), Behavioral Activation (BA)

Models

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

PRODUCTS

Accion

PRODUCTS

Acorns

Behaviors

Savings

Tactics

Framing Effects, Reduce Friction or Barriers, Automation +2 more

PRODUCTS

2Morrow Stress (and Anxiety) Program

Behaviors

Mental Health & Self-Care

Tactics

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), Behavioral Activation (BA)

Models

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

PRODUCTS

Advanced Brain Monitoring

PRODUCTS

AbleTo

Behaviors

Mental Health & Self-Care

Tactics

Personalization, Skill Coaching, Coaching or Counselling

PRODUCTS

ActiveLifestyle

Research on behavior change

PAPERS

Randomized Controlled Pilot Study Testing Use of Smartphone Technology for Obesity Treatment

PRODUCT

Lose It!

BEHAVIOR

Physical Activity, Diet & Nutrition

TACTICS

Education or Information, Reminders, Cues, & Triggers, Self-Monitoring or Tracking, Social Support, Feedback

PAPERS

Nutrition education worksite intervention for university staff: application of the health belief model.

BEHAVIOR

Diet & Nutrition

PAPERS

Pathway to health: cluster-randomized trial to increase fruit and vegetable consumption among smokers in public housing.

BEHAVIOR

Diet & Nutrition

TACTICS

Motivational Interviewing

PAPERS

The effects of a multimodal intervention trial to promote lifestyle factors associated with the prevention of cardiovascular disease in menopausal and postmenopausal Australian women.

BEHAVIOR

Physical Activity

PAPERS

Increasing screening mammography in asymptomatic women: evaluation of a second-generation, theory-based program.

BEHAVIOR

Other

PAPERS

Designing prenatal care messages for low-income Mexican women.

BEHAVIOR

Other

TACTICS

Education or Information

PAPERS

Enhancing the effectiveness of community stroke risk screening: a randomized controlled trial.

BEHAVIOR

Other

PAPERS

Value-Based Insurance Design Improves Medication Adherence Without An Increase In Total Health Care Spending

PAPERS

A comparison of two delivery modalities of a mobile phone based assessment for serious mental illness: native smartphone application vs text-messaging only implementations.

BEHAVIOR

Mental Health & Self-Care